CW: sexual assault, discussions of misogyny

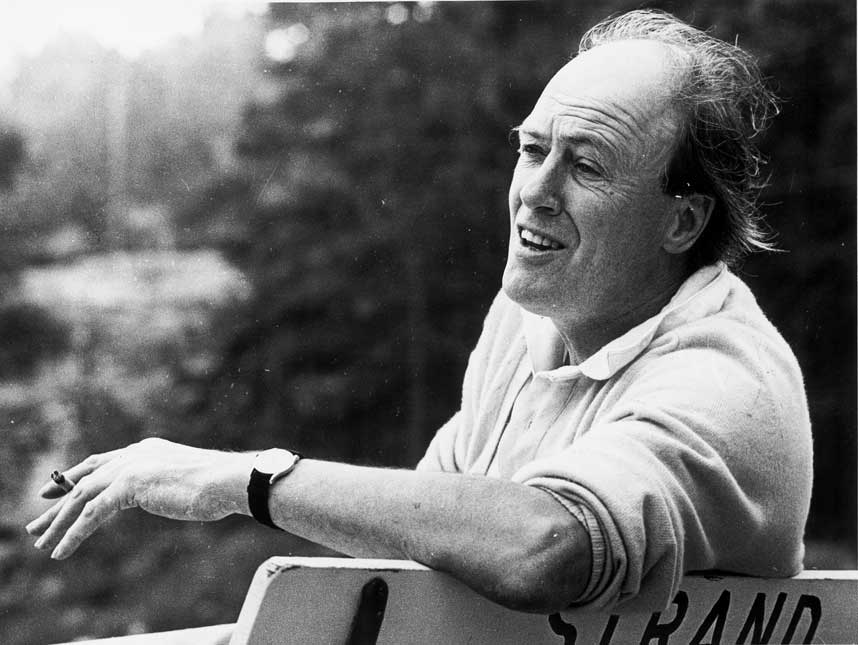

Few authors in British culture have as wide a fanbase as Roald Dahl. He is one of the most beloved authors of all time, and, in my view, rightly so. His work has an irresistible appeal, and I must confess to still reading his fiction aged eighteen, having left primary school a long while ago.

Still, few authors have as troubling personal backstories as Dahl does. The author’s short stories about his boarding school experiences make for horrendous reading. He nearly died from burns following an RAF plane crash, and in 1962, he lost his seven-year-old daughter to measles encephalitis. Amidst all that, Dahl casually wrote a string of children’s novels which revolutionised the genre. Multiple generations have inhaled his books in their childhoods. He was, without a doubt, a troubled, bitter, yet also ingenious, heartfelt man. After all, a common theme prevailing throughout his work (especially Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda, and Danny the Champion of the World) is the empowerment of the kind-hearted; a message applicable to ‘children’ aged nine to ninety.

Dahl also wrote macabre adult fiction. His children’s books are hardly light and fluffy, but his Adult Fiction is something else completely. Among his Adult pieces is the profanely entitled Switch Bitch, a collection of four short stories about sex, sadism, abuse, and scandal. It is possibly his most controversial work published.

Readers may know that Dahl posthumously receives much public press concerning his provocative personal beliefs. I have my views about whether we should blame him alone for those beliefs or rather blame the media of the time that produced him, but that is an article for our Opinion writers. My sole goal here is to examine the literary debate behind Switch Bitch. These four stories, titled ‘The Visitor’, ‘The Last Act’, ‘The Great Switcheroo’, and ‘Bitch’, have attracted both praise and controversy. Hopefully, I may persuade you to re-evaluate this very odd but, in my view, highly worthy piece of fiction.

Stylistically, these stories are conventionally Dahl. His turn of phrase, in which he conspiratorially invites the reader in as a close confidant, is a personalised narrative style that these stories don’t avoid. The style endows his work with the dark, wicked charm that makes it specifically ‘Dahlesque’. It is Switch Bitch’s story content that has had eyebrows raised among critics.

In ‘The Visitor’, the mysterious, womanising Uncle Oswald is stranded in Cairo, and a series of bizarre events culminate in a brutal twist ending. ‘The Last Act’ chronicles the graphic revenge of a gynaecologist on the recently widowed Anna after she rejected him decades prior. ‘The Great Switcheroo’ follows two men who experiment in attempting to sleep with each other’s wives without the wives finding out about the scheme. ‘Bitch’ brings back Uncle Oswald for a final tale about libido drug testing. Unconventional, to say the least.

In my view, this collection scores ¾. I found ‘Bitch’ slightly lacking, but the other three are phenomenal. The controversy focuses on the plots’ cruel, violent elements. Many things have not aged well, most notably the shameless womanising of the mysterious Uncle Oswald, by whom our narrator (his nephew) appears to be entranced. Oswald’s actions are, at best tasteless and, at worst, outright misogynistic.

However, defaming the entire story (and, thus, Dahl himself) by viewing it as ‘misogynistic’ is, in my opinion, a mistake. Upon completing the work, you will discover that Dahl is not wholly celebrating Oswald’s attitude. Arguably, he does the exact opposite. The story’s ending (no spoilers!) assures you that the message is patently not “Oswald has it right.” The ending of ‘The Great Switcheroo’ similarly leaves the protagonist with far more than he bargained for.

Similarly, I do not believe that Dahl’s other characters, such as Miss Honey, the feisty grandmother in The Witches, Mary Pearl (look her up), Mrs Foster (definitely look her up!), The BFG’s resourceful Sophie and, of course, the iconic Matilda are the creations of ultimate sexism. Or, at the very least, not of a man who actively seeks to promote sexist views through his work.

There are legitimate criticisms to be levelled at Switch Bitch, criticisms reduced of their nuance when we simply condemn the stories as fundamentally problematic. Consider ‘The Last Act’, where our protagonist Anna, recently widowed and emotionally vulnerable, is verbally and physically assaulted by a former flame. What, you may ask, is Dahl’s purpose behind writing this? Surely the average person goes to literature for entertainment and relaxation, not for sadistic tales of rape and torture? That is not entertainment.

This view is valid because literature is, of course, personal, and some people understandably avoid reading excessively violent stories. Equally, one could argue that for as long as women are abused and mistreated in the real world, literature should attempt to reflect it. Like in ‘The Visitor’, Dahl unequivocally condemns Conrad (the ‘Last Act’ rapist) as the villain. The entire story is told from Anna’s perspective, so her voice is far more prominent than his. By the time we reach the ending’s truly awful gut punch (where we see Conrad’s true intentions), our loyalties are entirely with Anna. These stories display brutality but never demand that we agree with it.

In short, Switch Bitch is twisted, unsettling, and highly worth reading. Dahl’s writing is as satisfying and bewitching as ever, and the collection also serves as a reminder of the most twisted, awful things that can happen in the world. Is it the master’s absolute finest work? No. But you certainly couldn’t call it forgettable.

Image credit: ‘Roald Dahl’ by Sally is licensed under (CC BY-NC 2.0)