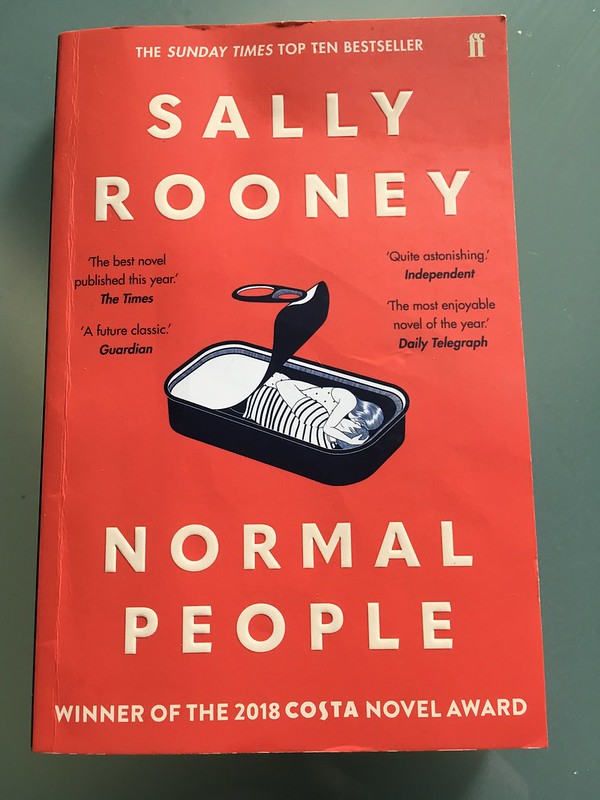

I love flawed female characters. As a big fan of contemporary literary fiction, I enjoy complex, well-written female characters and narratives about realistic, albeit slightly unstable, women. It can be validating to find relatability in these works of fiction. This is undoubtedly the appeal of authors like Sally Rooney, some of whose characters are endearingly relatable. Despite this, what began as a literary convention focusing on the everyday struggles of ordinary people, I believe, has morphed into a trend of glamorisation and glorification of female characters’ mental illnesses. It is a worrying sentiment seen increasingly in online readership discourse, particularly among young girls.

Recently, I saw a photograph of a book display in Barnes and Noble with the title “Gaslight, Gatekeep, Girlboss”. From that slogan, one would expect a supply of books about empowered, aspirational women, but as I scrutinised it, I was somewhat uncomfortable. How had Lolita, a profoundly complex novel about a twelve-year-old child victim, ended up here? Should we be viewing Gone Girl as a work of feminist fiction? And I’m going to hazard a guess that anyone could see why we shouldn’t be looking up to the cannibalistic female killer in A Certain Hunger. How had those who had assembled the display seemingly missed the point entirely of the books they had included? What is worrying is that it situates these novels under the pretence of female empowerment, and this is what consumers may have in their minds when it comes to reading them.

The glamorisation of female mental illness is neither the full responsibility of the author nor the reader but a combination of both. Sally Rooney frequently refers to her characters’ eating disorders while, in my opinion, never adequately addressing the issue. I think there is accountability here, for example, when writing for a readership of young women susceptible to such issues.

However, much of the problem stems from within the online community of readers, those who sensationalise and glorify the mental illnesses of female characters. Perhaps the best example of this is online reactions to Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, whose narrator is a disturbed and somewhat bigoted woman who abuses prescription drugs in an attempt to sleep for a year. In fairness, Moshfegh makes this clear in her novel. Why, therefore, do hundreds of women online hail the novel for the character’s relatability and recommend it to other young female readers? There has, similarly, been a renewed fascination with The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath, with readers desperate to relate to the characters and their mental illnesses, which I find neither quirky nor positive.

Books have power. That power stems from what is written in them, what we take from them, and how we share them with others. It is inspiring that fiction can be used as an outlet for discussions around mental illness and the complexities of human emotion. We must, however, be careful not to allow ourselves to glorify these conditions under the guise of relatability and collective female experience.

Image Credit: “Normal People by Sally Rooney” by felibrilu is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.