I recently came across a short poem in which Chaucer wishes upon his scribe a scaly scalp if he continues to write up his work incorrectly. ‘So ofte adaye I mot thy werk renewe,/It to correcte and eke to rubbe and scrape,/And al is thorugh thy negligence and rape.’ he writes in ‘Chaucers Wordes Unto Adam, His Owne Scriveyn’.

It isn’t often that we hear his voice unmediated by layers of narration. He isn’t playfully hiding behind the characters he speaks through. This is Chaucer the poet, not Chaucer the narrator, pilgrim, nun, or knight. It is an exasperated poet imploring his scribe, very cheekily, to write up exactly what he has written so that he isn’t forced to scratch out mistakes with a knife or stone. This insistence on accuracy was unusual for a time where authorship was more fluid.

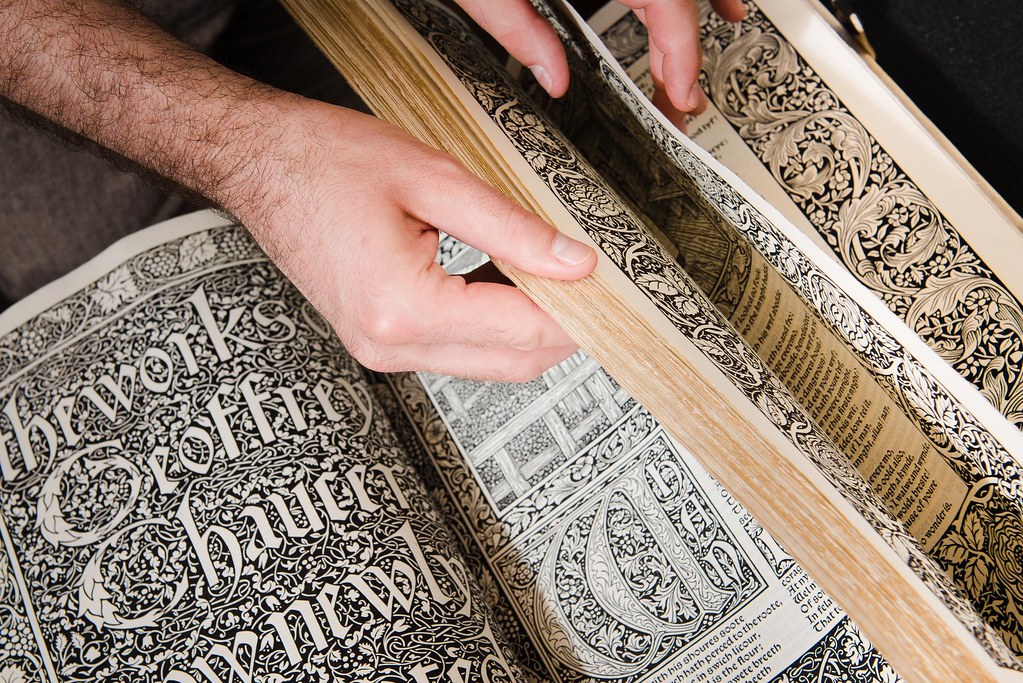

Since the advent of print culture, writing has become an increasingly direct process. From the author to the reader, once it is published. Reading happens in our heads. Authorship is king. Readers want the author to speak to them alone, and they want to get to know them. But it was once just a man sending words out into the world, to be copied and told and copied again.

We have three main manuscripts of The Canterbury Tales. Each one is different, even down to the order of the stories. What we know of The Canterbury Tales is not what Chaucer first sent out to his scribe. So, behind these rich intelligent tales, remember Adam, his poor, sloppy, and possibly now scaly scribe.

Image: UBC News via Flickr