COP26 has sparked a fiery response from creatives the world over. Filmmakers, poets, and artists are all expressing their growing concerns about the indifferent response to the climate crisis, and the conference’s Green Zone Programme has been packed with performances, screenings, and panel discussions with leaders in the arts. In the literary world, climate change fiction is slowly beginning to pick up, but its wakening is surprisingly slow.

Almost every major social and political change in the last few centuries has been accompanied by literary responses and movements, and today, such works are studied for their usefulness in formulating thoughts—the right thoughts, more importantly. Hence, the unquestionable importance of teaching anti-war poetry, slave narratives, Romanticism, postcolonial literature, and so on. Writing has made abstract threats (and one could argue that the climate crisis is the most abstract of all) pertinent for societies otherwise engaged in running themselves. Therefore, climate fiction, or ‘cli-fi’, as it the genre is often called, potentially serves the crucial purpose of making the remote effects of the climate crisis familiar—the only way for American consumers of palm oil to hear the stories coming out of the drowning Sundarbans.

Certainly, climate change has featured in literary fiction, albeit mainly in the form of sci-fi and dystopia. The most famous early examples of this would perhaps be J. G. Ballard’s The Drowned World and Frank Herbert’s Dune. One is set in a post-apocalyptic future and the other literally on a different planet. The idea, previously, appeared to be explore an imagined world, a familiar but not too familiar place, racked by problems that were clearly in the making, and had not quite been felt yet. Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140 is a perfect example, considering a metropolis underwater and the social consequences for its inhabitants. Even now, the language of climate change discourse is overflowing with the vocabulary of dystopia: the end of the world, the unthinkable, emergency,

The problem is that climate change can no longer be relegated to fantasy and sci-fi. It has become a crisis of now, not the distant, or even the near future. Cli-fi is inadequate in capturing Californian wildfires, Indian floods, and continental heat waves, all of which sound like disasters straight out of sci-fi novels, and yet have taken place in the past three years. Often, the simplest experience of climate change is a flooded house. Or a disappearing park. Or haze.

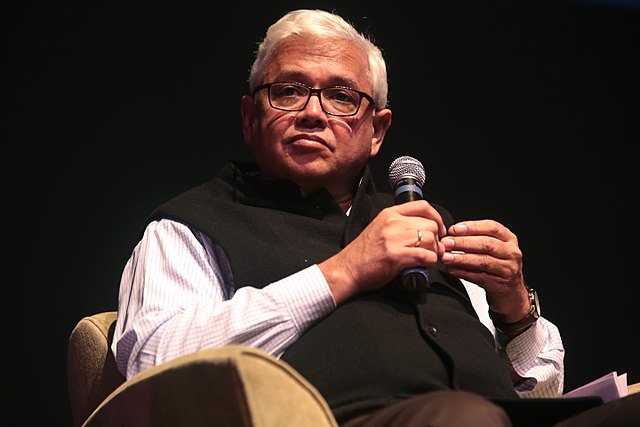

In his landmark polemic, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, Amitav Ghosh points out just this, going further in stating that cli-fi is often simply reduced to sci-fi by critics and the reading public at large. in which he points out just this fact. He even directs this criticism at himself for only obliquely tackling the subject in his previous work. Even now, climate change is widely covered in non-fiction. There are books upon books covering the data, the reportage, and the scientific solutions relating to the climate crisis. The most famous of these is probably Bill Gates’ How To Avoid A Climate Disaster, pivoted on the science behind tackling climate change. It is a real problem, an existential problem, and yet not human enough for serious fiction to accommodate. Very prominent writers have begun tackling the subject, such as Margaret Atwood, whose MaddAddam trilogy looks at a world reeling from a biological catastrophe.

That being said, there is some slow progress being made. Speaking with the Guardian, Ghosh described the turning point in this field to be Richard Powers’ Pulitzer-winning The Overstory, a work of realist fiction with strong environmentalist undertones and themes. Kim Stanley Robinson himself also published The Ministry of the Future last year, set in a near future and centred around the Paris Climate Accords. Unfortunately, it is becoming easier for writers to chronicle the effects of climate catastrophe without having to imagine them up. Ghosh himself published Gun Island in 2019, using myth and folklore to look at climate change and human migration. Despite the human tragedies and the environmental devastation that follow bungled climate policy, artists and writers have always been able to take old problems and reshape them in new ways, draw out new perspectives. It is safe to say that, despite its slow start, literature will begin to speak against climate change inaction more strongly, and the climate crisis will become the prime preoccupation of writers across the world. After all, surely it must?

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons