The history of Scotland’s capital is mostly rich, varied and deeply enthralling, yet unfortunately, when it comes to its association with slavery, Edinburgh possesses a still visible, disturbing legacy. As a nation, there is a sense of collective amnesia surrounding Scotland’s involvement in the Transatlantic slave trade. It is time we acknowledge our collective responsibility to remember and raise awareness of such issues. Scottish merchants and plantation owners played a huge role in this abhorrent trade, with Scots making up one in five slave owners stationed in Liverpool. Furthermore, though Scotland was vital in the colonial escapades of the British empire, in the 1690s, prior to the 1707 union, Scotland did in fact attempt to establish its own colony on the Isthmus of Panama called ‘Caledonia.’

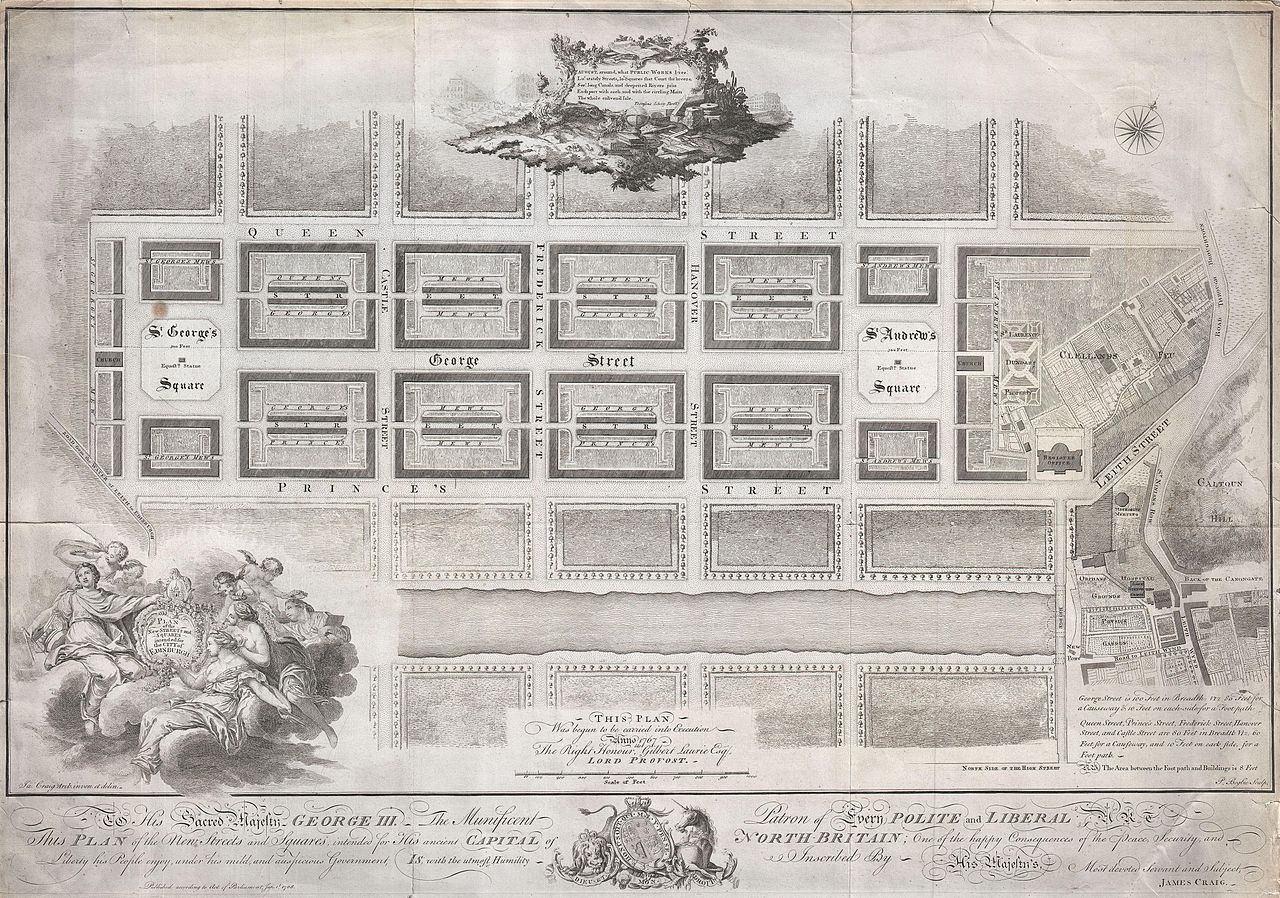

One of the most obvious examples of Edinburgh’s slavery associations is in the architecture. Many of the streets of Edinburgh are lined with ornate Georgian architecture, foundational components of the New Town’s architectural character. Yet these are tainted with disturbing origins, plenty of the properties being built in the mid-eighteenth century with the wealth accumulated from the trade in human labour and inhabited by the wealthy merchants and plantation owners who perpetuated the trade.

After the abolition in 1807 and emancipation in 1833, the British government compensated British slave owners for what was seen as their loss of property, amounting to a colossal £20 million, 40 per cent of the national budget. Sir Geoffrey Palmer, emeritus professor at Heriot-Watt University and human rights activist, has observed that large quantities of the benefactors recorded on the compensation list resided in Edinburgh. The list included 320 Edinburgh addresses belonging to 148 individuals; the majority in the New Town. The evidence of the compensation is even visible today with the properties that appeared on the compensation list appearing visually more ornate, the residents being able to invest their profits or compensation payments into additional architectural embellishments, such as balconies or extra doors, to display their immense levels of wealth.

John Gladstone, the father of former British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone, was one well-known figure who benefitted, receiving £93,526 in compensation for his 2,039 slaves. He is a prominent example useful in illustrating the exceedingly large magnitude of wealth the Scottish claimed through the slave trade, owning some of the largest plantations across Jamaica and British Guyana. His son, William Gladstone achieved a successful 60 year parliamentary career, serving four terms as prime minister, and was remembered for his liberal policies, however it is arguable that such success, would have been unachievable if it were not for the privileges and political connections he experienced as a direct result of his father’s plantation compensation. Ironically, Gladstone’s political career, which attempted to push to improve the lives of the British electorate, came at the cost of atrocious human suffering overseas.

A further example of Scotland’s slave trade association is in their export of goods. One of Scotland’s most lucrative exports at this time, crucial to the domestic industry, was the trade of ‘slave cloth.’ Linen production has long provided economic prosperity and a way of life to the Scottish. During the 18th century, linen manufacturing was the largest industry in terms of employee figures, with 90 per cent of all Scottish linen exported to North America or the West Indies. While Scotland was also involved in the manufacture of higher quality fine lawn cambric linens, its primary production focused on the cheap, coarser fabric, known as slave cloth, which was exported in vast amounts across the Atlantic to clothe the enslaved workers on the Scottish-owned plantations. The British Linen Bank, whose roots lay in the Scottish linen industry, stood on St Andrews Square; now the Royal Bank of Scotland.

Even some of Edinburgh’s schools remain gripped by Scotland’s colonial past. The founder of the James Gillespie High School was a well-known philanthropist. Upon his death in 1797, he bequeathed a quarter of his wealth to establish the school for the education of poor boys. He was nonetheless, a highly successful tobacco merchant whose profits were made at the expense of chattel slaves working in the West Indies.

Recently discussions have taken place across Edinburgh as to whether to remove entirely or alter the information plaque on the 42m high Henry Dundas statue in St Andrews square. Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, was a Scottish Tory Politician. Yet in 1792, as Home Secretary, Dundas sought to amend Wilberforce’s abolition bill with his addition of the word ‘gradually,’ thereby changing the House of Commons’ pledge to ‘gradually abolish the slave trade.’ His malicious intervention significantly delayed the date of abolition by another 15 years. Though it is argued that the act of tearing down statues, is an attempt to erode history itself and thereby also problematic. It is integral that the full story is told, to make the true legacy of figures such as Dundas accessible to the city’s residents and visitors. This is our history and we deserve to know the truth, giving us the agency to encourage future change.

Glasgow University has begun a process of reparative justice after research disclosed how significantly the institution benefitted from the slave trade. While the university itself did not advocate the enslavement of individuals or trade in goods the system produced, it did receive large financial backing from many benefactors whose profits were derived entirely from the slave trade. There are now plans to install memorials on campus, create a centre for the study of slavery and establish strong ties, promoting scholarships, with the University of the West Indies. Given Edinburgh’s entangled links with the slave trade, it would be interesting to discover whether our university holds a similarly dark history.

It is important to recognise and celebrate the architecture throughout Edinburgh, it is crucial we do not sugar-coat the truth behind their origins and remember they arose at the cost of an appalling history of human suffering. Like any observation of history, we cannot change the past, but we can increase awareness in an attempt to change its consequences.

Image: Geographicus Rare Antique Maps via Wikimedia Commons