There is an inherent danger to reviewing a performance by an artist you like. It punctures the veil of objectivity that I, a humble reviewer, seek to maintain analysing what I have witnessed. Yet it is no different than that of reviewers choosing comedians they like, or even their own friends. In that spirit, consider this piece a reflection on why you too should be a fan of John Cale, using Saturday’s performance at the Edinburgh International Festival as a point of reference.

As a founding member of Andy Warhol’s The Velvet Underground, Cale was the instrumental backbone of the Underground’s sound, a bassist, pianist and viola player whose ear for drone and harmonising stood out from all other music around it. Though commercially limited in its early reach, Brian Eno later commented that everyone of the 30,000 people who bought their debut album went on to start a band – their legacy namechecked in krautrock, shoegaze, punk, and anything considered remotely indie. Faced with such a moniker of respect within the industry, there is a joy in listening to an unknown Cale track – such as his set opener Jumbo in Tha Modernworld; the initial attempts to categorise and understand where the song sounds familiar from, before then recognising that it was likely Cale and the Underground’s work that spawned the inspiration.

But in his long solo career, Cale has established a reputation far beyond his drug-addled juvenile adulthood, his most successful hit Paris 1919 the next track to bring whooping to the heterogeneous audience, packed to the rafters of the Festival Theatre to hear their musical godfather deliver. Paris 1919 is baroque in its approach, giving way to the verse-chorus-bridge format on a lyrical adventure reflecting on the personal observations of a character in the First World War. It was red meat to the crowd, bracing for the curios that undoubtedly lay ahead.

Key to Cale’s appearance was his new album released earlier this year, Mercy, a seventeenth solo effort that pulls Cale’s quivering voice over pumping synthesisers, vocoders, and steady distortion. It echoes the dying Bowie albums, its lyrics harrowingly damning of the present, its instrumentation as reflective as Sigur Ros, the music not so much being listened to but absorbed in. When performed live however, there is no concern over a quiver. At 81, Cale’s voice remains defiant, carrying force in delivery, weight through the hall. His voice has always been something of an oddity, the soft Welsh tongue of a coal miner’s son with a slight American lilt, his singing a provocative stress over the musical arrangement as opposed to a smooth harmony. He is not Lou Reed, not that he ever wanted to be.

Among the work exhibited from Mercy are its eponymous title track, and Moonage Junkie, a tribute to his troubled friend Nico – the sultry vocal counter to the Underground’s rough output. Each track is long, observing our song conventionalities before twisting the instrumentation into spells of controlled anarchy, each instrument and artist playing with one another, tooling the possibilities that can emerge from the set menu of each track. Supporting Cale are a drummer, bassist and guitarist, the last of whom later used a bow on Cale’s behalf. Together, they drew from influences as diverse as reggae and punk in transforming Cale’s ivory tickling into a complete work of art. Under guitar distortion, the drone effect is powerful, better evoking the Jesus and Mary Chain than the Cocteau Twins, enveloping the hall under a spell of nodding heads and tapping feet.

In a nod to variation, Cale returned to his catalogue with Barracuda, a song fifty years young next year, a frustrating lament of all that can be swept away by external forces, again distorting its chorus and playing into a chaotic coda, evolving beyond what would otherwise be a nod of acknowledgement to his intelligent audience. Yet here stood a master, a man content to walk away after barely an hour and a half, only to return after five minutes of whooping applause and cheering. Lights had gone up, people had left, yet the devotees demanded an encore, so who was Cale to deny them? His choice was Heartbreak Hotel, radically reimagined from its rockabilly roots to move the most stoic in the audience to tears. Melancholy and dour in its reflections, the standing ovation that succeeded it closed out a night of unrequited affection towards the great survivor of old school music, the elder statesman of all that is new music.

For his part, Cale was largely ignorant of the audience in front of him, a gruff thank you and a solemn wish to ‘see us again sometime’ enough to maintain societal expectations. After all, Cale – more than maybe anyone else – could let his music do the talking. This audience, present company included, were in awe just to be able to listen.

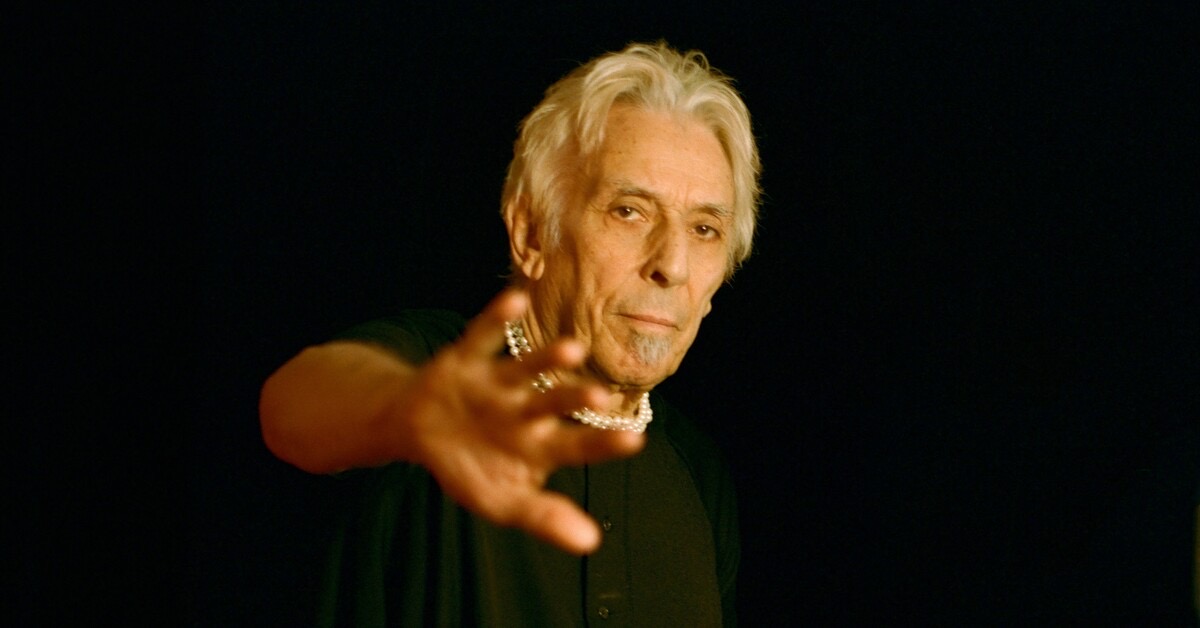

Image courtesy of Madeline McManus, provided to The Student as press material.