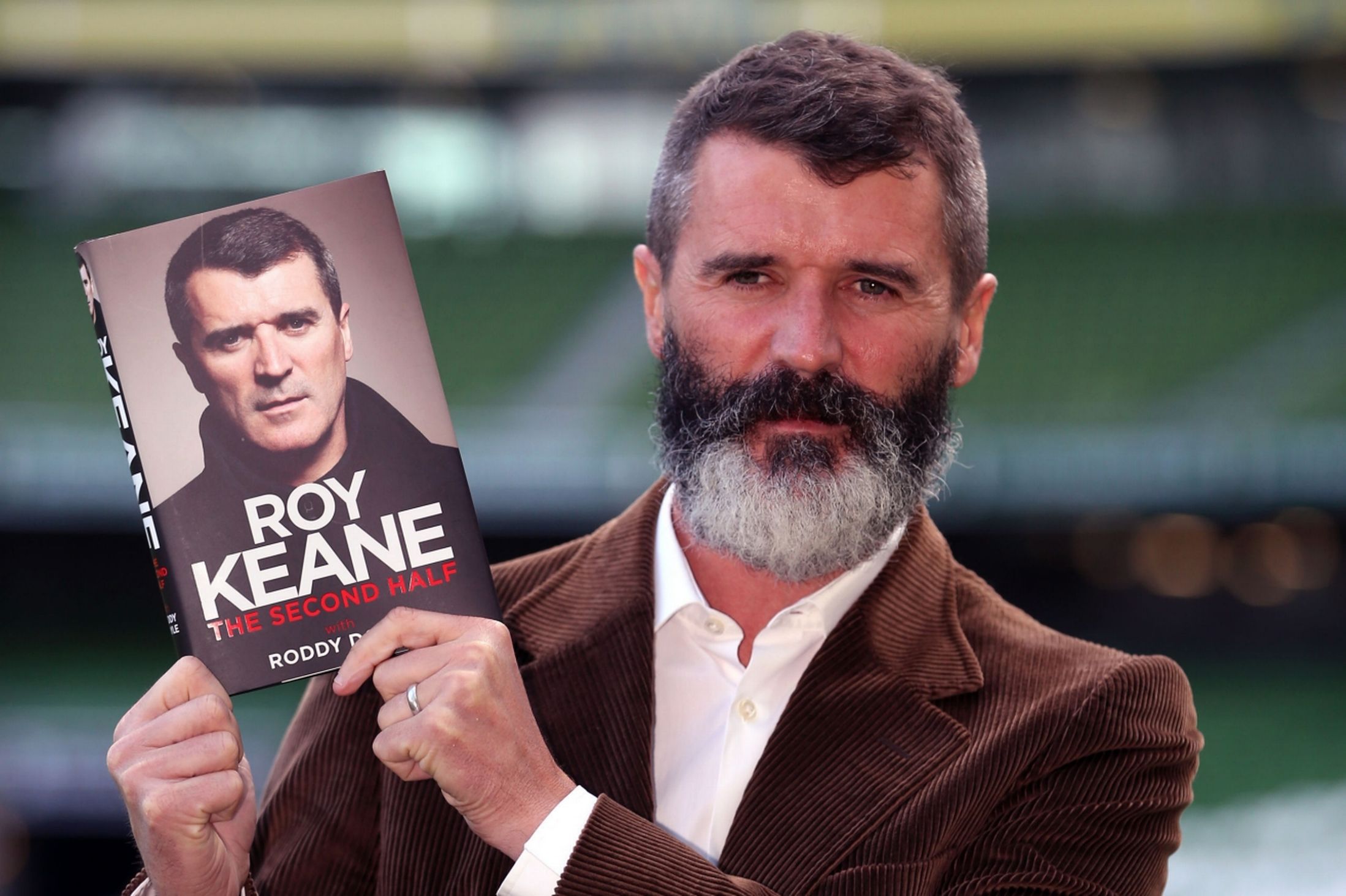

There’s an enduring image that I can’t shake when reading Roy Keane’s much publicised and much vaunted autobiography. Roddy Doyle, Roy’s unlikely but inspired choice of ghostwriter, throwing his pen in the air, half amused, half in despair. Recognising that having spent a lifetime creating critically acclaimed, Booker Prize award winning characters of working class Irish stock, he would never have dared to create one so baffling, yet so brilliant, as the one sitting in front of him. The truth scarcely more believable than fiction.

The Second Half is a book that contains some fascinating stuff on the trials and tribulations of football management, some typically and much anticipated ferocious score settling, and a collection of anecdotes and dry wit that will leave you gasping for breath. In short, if you’re Greg Halford, do not, under any circumstances, read this book.

Lurking below the surface, however, is a riveting insight into a divisive figure whose difficult and thorny relationship with the media may have tricked us all into a blind alley of hearsay and misconceptions. The Roy Keane here, is, certainly, a fiery figure, but also on reflective, self-critical one. He talks openly and without inhibitions about his failures both as a man and a manager. There a few themes that stand out, however. Each of them helping to weave a tapestry of a man imbued with old fashioned values in a rapidly changing industry.

Firstly, a passage in which Roy talks of an encounter with the Dutch striker Ruud van Nistelrooy on the morning of an FA Cup Semi-Final. Ruud, struggling with his knee, decides to sit out the game. Keane, himself battling with an injury, is totally baffled. Keane plays, Ruud doesn’t.

Keane notes that Ruud would go on to play for another six or seven seasons after him. A reflective Keane now reflects what he thought was a sign of weakness on the part of his foreign teammates was indeed intelligence, his macho bravado reckless and damaging.

Indeed, this book provides a fascinating insight into changing conceptions of masculinity in sport, particularly in such a working class dominated game. Keane is, like any classic male Doyle character and as you’d expect of a man of his background, unashamedly macho. He revels in, and eulogises on, his battles for supremacy in the centre of the park, confrontation on and off the field. He talks in parts of his need to go out and earn for his family, to set an example to his children. The Van Nistelrooy tale demonstrates, however, that he is savvy and smart enough to realise that the nature of football is changing, and being the domineering male figure brings as many problems as it does positives.

In a sport under enormous external pressure to adapt, open up, even soften up, this insight from one its most respected protagonists is deeply illuminating.

Similarly, his perceptions of the changing rooms he inhabited as manager and a player are riveting. Withering in his assessment of the new dressing room culture, focused less on each other and more on their headphones. A lack of leadership, responsibility. He speaks of warmth for his Championship dressing room at Sunderland, hard-working and dedicated, who ‘had a go’ and ‘ran til they dropped.’ He laments a sense of loss when the Premiership riches came and the squad, laced with new, expensive products, lost its fire.

This feels important because, broadly, football fans want their game to change. More inclusive and turn the Keys, Terry era into a relic. Yet whilst there may be no bad thing in football losing its macho culture a little, and Keane is the first to recognise the wonderful effect the influx of foreign influence and expertise has had on the English game, there is no reason why it shouldn’t still venerate hard work, leadership, desire, hunger and team ethic. Roy Keane, love him or loathe him, embodies that.

The game needs him, it needs that fire.

There is one more passage that sticks with me. A Championship game between Leeds and Sunderland. Gus Poyet, then Leeds Assistant Manager, throws a ball onto the pitch as Sunderland attack. I went home incensed that day. Worst display of gamesmanship I’d ever seen. Now, ask me about Gus Poyet and I’ll tell you how much I admire his tactical nous, how he has turned my club around. This is a stark reminder that football brings out the most impulsive, extreme emotions in all of us.

That this book presents us with a fuller, more reasoned picture of this supremely talented footballer is surely welcome. In the end, we are presented with a man who has spent his career pushing his peers into walls, demanding more, always looking for an extra five percent. Some have taken it well, some haven’t. A man not without flaws, but with a redeeming talent and drive. Vintage Roddy Doyle. He must have made it up.