Growing up in twenty-first India, a nation nursing the wounds of its harrowed colonial past, provides an insightful overview into how the wheels of liberation movements are carried across intergenerational timelines. Seventy-two years since India disentangled herself from her colonial clutches and emerged independent, everyday stories of everyday people standing resolute, injected with valour, having adorned an impressive shield of bravery to liberate themselves, are still enthusiastically shared. These stories are passed onto children as bedtime tales, shared along with the sweet aroma of cardamom chai in the evenings, while drying laundry on the semi-attached rooftops, during a nail-biting game of gully cricket. These stories about gaining liberation revolved particularly around two of the largest non- violent liberation movements — the Salt March and the Swadeshi (freedom) movement. Observing how these movements involved everyday people in their everyday routines is intriguing, as we see how the idea of liberation spills into the grassroots and everyday sociological patterns.

Quite frequently, I hear an iconic story of my grandfather, who as a young adult, burnt all his new and rather expensive silk shirts (a rare commodity at that time) that were fondly gifted to him. He did this in order to stress the idea of being liberated from heavy textile taxes imposed on the masses. The sheer volume of these stories are quite interesting. The tales generally oscillate between stages of being repressed and a sudden outburst of vigour. While romanticised tales instil a feeling of identity especially across generations, it is very easy for them to filter into a disdained picture, far from reality — resulting in consequences, unknown.

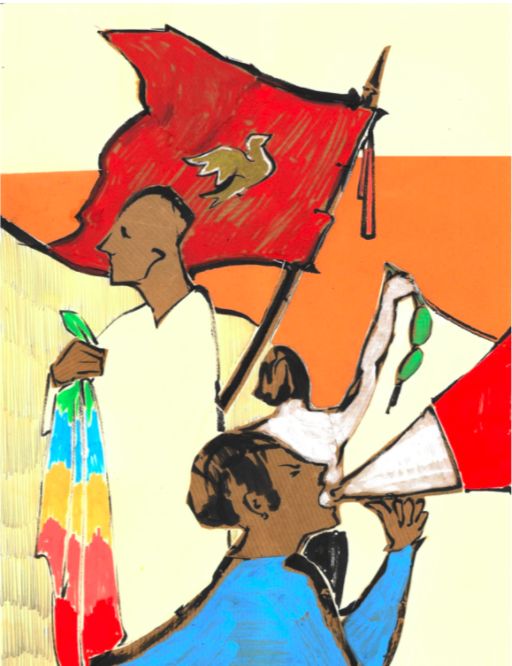

The impression and impacts of these stories can inspire people to fight against socio- political or economic inequalities that may hinder them. Using visual components and historical remnants that reflect cultural pride, identity and defiance widen the scope for people to express their animosity against systems. The trickle-down effect should revolutionise and transform global liberation movements into a more inclusive ground, by bringing together individuals from all lengths and breadths of a spectrum. However, realistically it is difficult to consciously break down unconscious biases and predisposed notions.

While bringing together thoughts, beliefs and impressions from a spectrum, the liberation movement in its ever-expanding capacity would encounter rather nescient perspectives that can be hard to process.

Recently, I was in a quaint Scottish town and happened to visit the local museum. I observed children colouring pictures that shockingly demonstrated a situation that would instantly be deemed politically incorrect, as they clearly depicted a scenario of racial inequality. After having questioned the manager about this, she told me that the thought had never come to her mind and wanted to take initiative to change it instantly. Meanwhile, another member of staff challenged my point and narrated some first-hand experiences of having worked as a colonial officer in Malawi, passing some very questionable comments. His worldview predisposed him to think there was nothing wrong with this depiction of colonialism. I put forth my line of thought. He patiently heard me out and after a long conversation, thanked me for my perspectives and said “This is shocking because that’s what I have heard all my life.”

Sharing stories and expressing the importance of liberation in everyday lives can also create echo-chambers of thought, insulating groups from expanding their ideas.

Looking through the lens of liberality, it is interesting to investigate when oppression begins and whether it is inherent to human society. A thought-provoking question to analyse is how to accelerate the process of liberation when one isn’t aware of having been oppressed? From a transcultural perspective, one may be oppressed in a particular structure but not necessarily the other. So, to be able to join a global liberation movement, one would have to not only be able to view their position in different societal structures, but also be empathetic and consciously gain a panoramic range of perspectives to broaden the scale of inclusivity.

In light of the technological era, how do we use artificial intelligence to curate liberated digital spaces? Access, movement-building and resistance forms the praxis of liberation movements.

As our online lives become an extension of the offline, these pillars are crucial in ensuring that liberation movements are strong, inclusive and all-embracing. Enabling access to the internet and information is the first step to providing people with a platform to join the movement. This then ensures that movement building is carried out in a sustained, accountable and transparent manner and one that facilitates an environment of respect and mutual understanding. While constructing digital economies, it is also necessary to weave in intersections of the liberation movement, to create more inclusive spaces for the consumer and producer. Furthermore, in regards to freedom of speech in digital spaces, it is also vital to engage in discourse concerning liberation, so that regressive and extremist forces are muted. Granting wide representation in digital legislation would ensure that moral policing and censorship laws do not restrict expression of the cause at hand.

However, viewing the way algorithms work, it is still very easy to slip into a bubble of opinions only favourable to our own personal views and thus the burden is on the individual to make that difference. For example, by making the effort to look up an alternative news platform, or explore a new art page. These stories of liberation and their subsequent historical impressions help us believe that this feeling of liberation exists within all of us. Keeping this in mind, in order to metamorphose, to continue expanding one’s horizon of thought, we must look beyond our own immediate oppression.

In doing so, we would receive a kaleidoscopic outlook towards the world, thus enabling us to tackle everyday issues, a necessary foundation for creating a wider global phenomenon.

Illustration: George Williams