Two new studies reveal that a single mutation in the Ebola virus may have been responsible for its devastating effects during the recent epidemic.

The mutation, known as A82V, appeared in early 2014 and has been found in over 90 per cent of the viruses sequenced during the epidemic.

Some viruses, including Ebola viruses, are coated with an envelope that contains molecules called glycoproteins. Glycoproteins recognise and bind to specific sites on a host cell to allow the virus to infect it.

In humans and other animals, Ebola viruses recognise and bind to the protein NPC1, which allows them to enter the cell. But every species has a slightly different NPC1, and some viruses are better at binding to certain versions than others.

A82V is a mutant Ebola glycoprotein that preferentially binds to human NPC1 rather than that of any other animal. Having this mutation meant that an Ebola virus would be uniquely geared to infect humans instead of its original animal reservoir, fruit bats.

“The mutation makes the virus more infectious”, says Professor Jeremy Luban of the University of Massachusetts Medical School: “It arose early in the outbreak, perhaps three or four months in.”

Scientists from the US and UK also showed that viruses with the A82V mutation were not just more infectious, but could also have been more deadly. Studies of Ebola cases from Guinea showed that there was a significantly higher risk of death associated with A82V compared to the original glycoprotein.

However, they are cautious of blaming it all on the mutation, since there are many other factors that could have contributed to the fatalities.

Researchers from Europe, Australia, Africa and North America also teamed together to discover how the virus behaves differently in bats and in humans. They also found, in addition to A82V, there was a combination of other changes that led to increased infectivity in humans.

Instead of a single mutation event being the reason the Ebola virus became so devastating to humans, they argue that the virus continued to evolve and adapt to its new human hosts. A82V may have just been the first step.

“When a virus is introduced into a new environment, a new niche, it will try to adapt to that new environment,” says Professor Jonathan Ball from the University of Nottingham.

But was the severity of the outbreak directly caused by the mutation, or was it just an unhappy coincidence? Despite recent evidence, scientists think it may be impossible to say.

The A82V mutation seems to have arisen just as the virus spread from Guinea to Sierra Leone in early 2014. However, without replicating the epidemic exactly, we simply cannot tell if the Ebola virus spread so fast because of the mutation itself, or because of any other circumstances that surrounded it.

“Answering that question conclusively is probably something we cannot do,” Professor Luban says: “[But] it is hard to imagine the mutation was not relevant.”

Regardless of the direct cause, these studies only highlight the need for effective strategies in dealing with epidemics, to prevent infectious agents from further adapting to humans.

Rapid, targeted public health interventions can be improved by better surveillance and understanding of the link between genetic changes in a disease and how they affect humans.

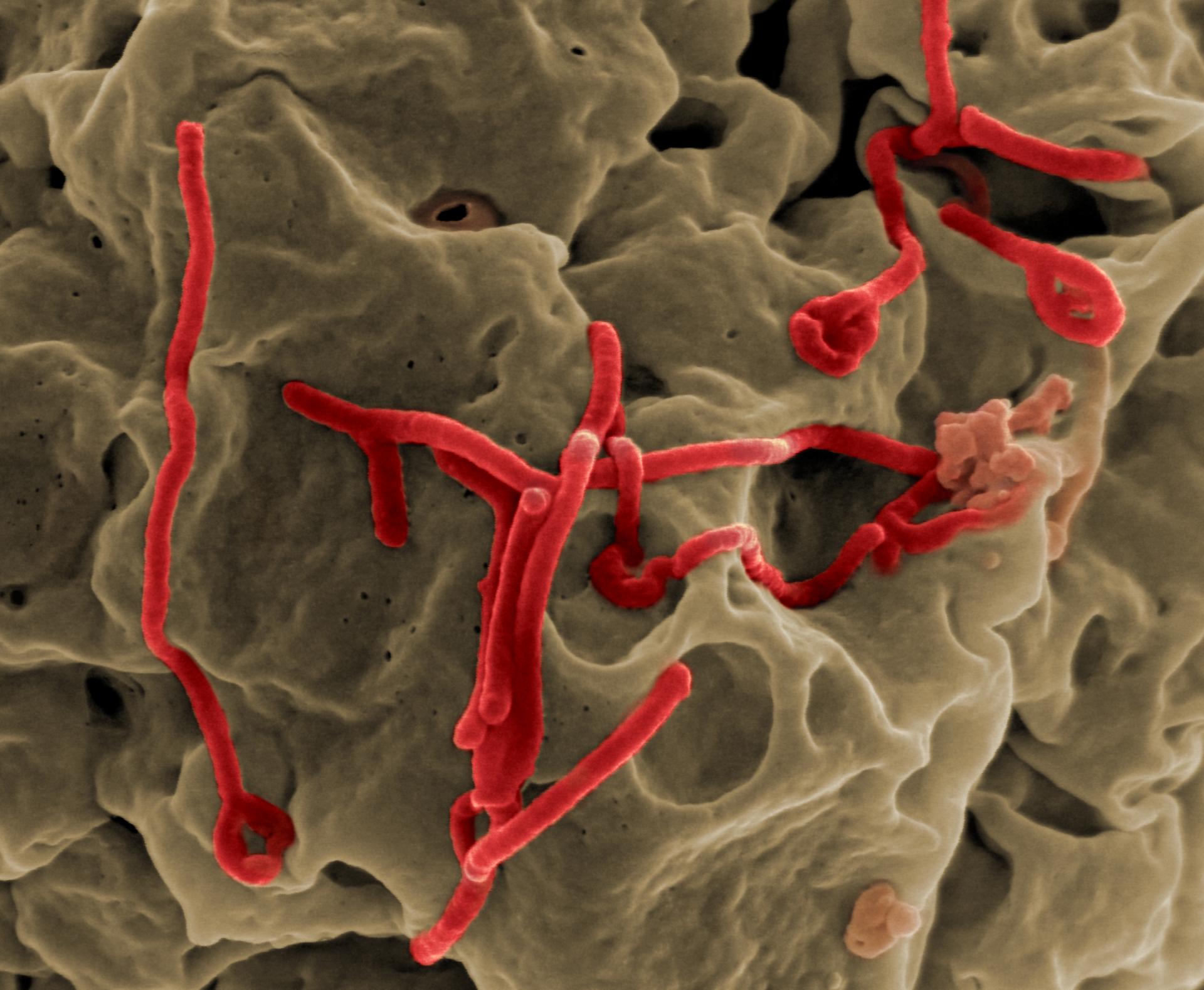

Image: – Ebola Virus