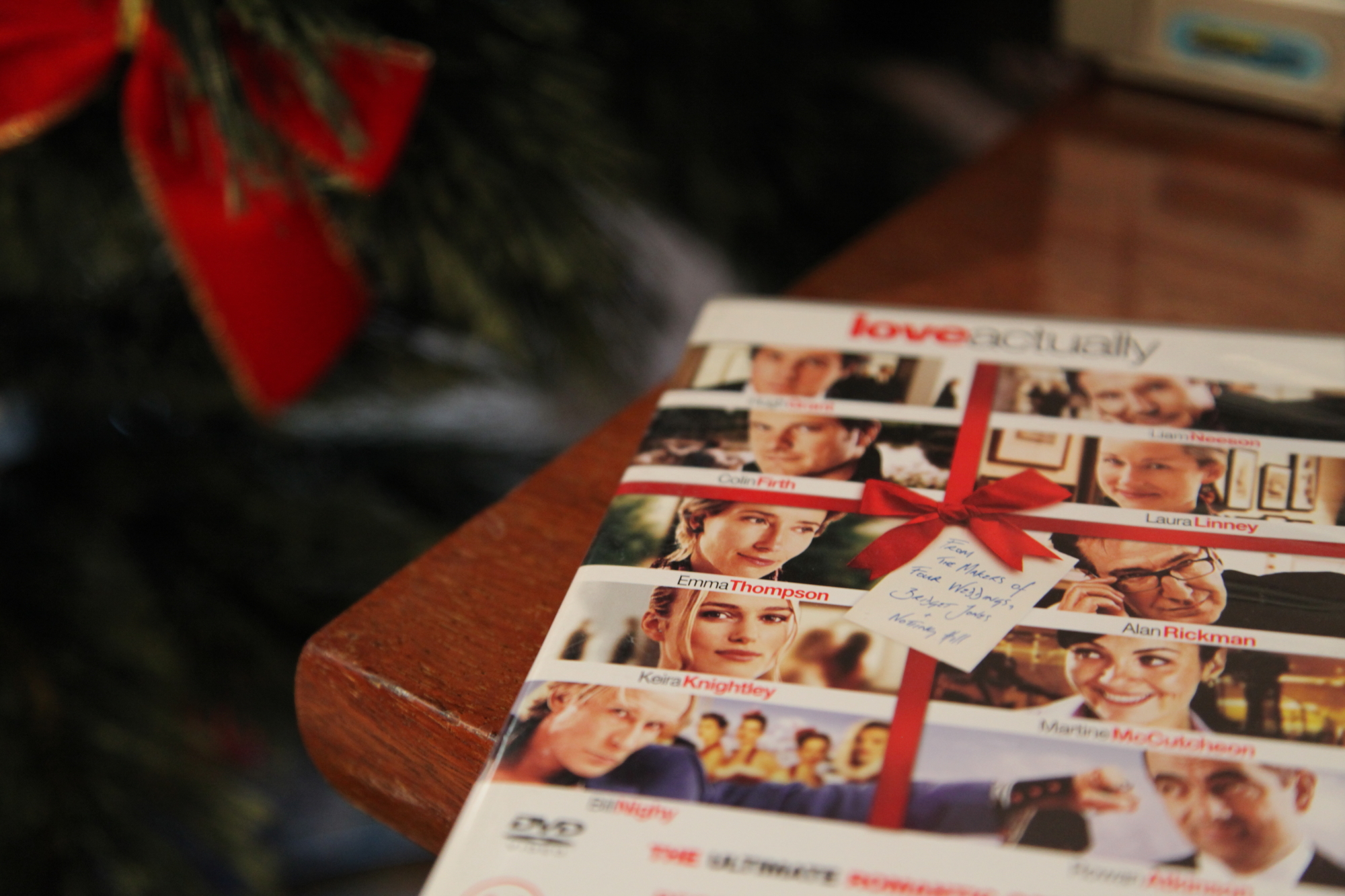

Writing this on the 1st of December means it’s now acceptable for the annual viewing of Love Actually to take place. This perennial seasonal classic is, at first glance, everything you need in a Christmas film. The cast is a roll call of national treasures, it makes London look sunny in December and the knitwear is second to none. But much as I do love this film, actually, it’s impossible to overlook its blatant erasure of LGBT+ characters.

As I’m sure you’re aware, Love Actually is based around an extended group of friends, families and colleagues whose stories are all interlinked. Remarkably, not a single one of the relationships portrayed is non-heterosexual. There’s not even a hint of a coded queer character; this group is a wild statistical anomaly.

It’s worth noting that a lesbian love story was filmed, but didn’t make the final edit. In true bury your gays fashion, one of the women is terminally ill. A Classic queer subplot. The deleted scenes are touching and intimate, and it’s hard to see a good reason for this plotline being cut in favour of the any of the straight ones. I’d much rather watch this genuine relationship than the uncomfortable threesome between Creepy Mark, Keira Knightley and his unnerving secret wedding tape.

Love Actually is by no means unique in this. From The Holiday to Michael Bublé aggressively heteronormative gender swapping of the ‘Santa Baby’ lyrics, Christmas media is largely very straight. No matter what festivals you celebrate, holidays are a potentially tricky time for LGBT+ folk. For those who aren’t welcome home for the holidays, or those who have to hide their true selves from their loved ones, Christmas can be an isolating experience. The last thing queer folk need is having any feelings of not belonging confirmed by their erasure in most Christmas media.

The underlying message of this erasure is that Christmas is a time for family in its most ‘traditional’, nuclear sense. There is no place for queer people this this narrative. The fact is, the nuclear family is a long dead institution, and media representations need to evolve to reflect the variety of family units that exist today. The most frustrating aspect of Love Actually is that in filming a queer plot, Curtis acknowledged the presence of these characters, before deciding that they were the least important and could therefore be compromised. Representation is vital for all groups who have long been excluded from the dominant narrative. We need Christmas films that show young queers at this time of year that their love and their families are just as valid and important as their heterosexual peers. We need to see queer couples exchanging gifts under their tree. We need to see same sex partners being brought home to meet welcoming parents. We need a queer John Lewis advert. We need normalisation of queer relationships, because seeing your own story on the big screen is a powerful experience. The association of the ‘tradition’ of Christmas with straight couples kissing under the mistletoe is at best heteronormative, and at worst homophobic.

Love Actually was released 14 years ago, and whilst queer media representation is slowly improving we still have a long way to go. As a turtleneck enthusiast, I won’t be boycotting this year’s viewing, but I will be considering the flaws of this film and watching Todd Haynes’s Carol on repeat to compensate.

Image: Kate Ausburn via Flickr