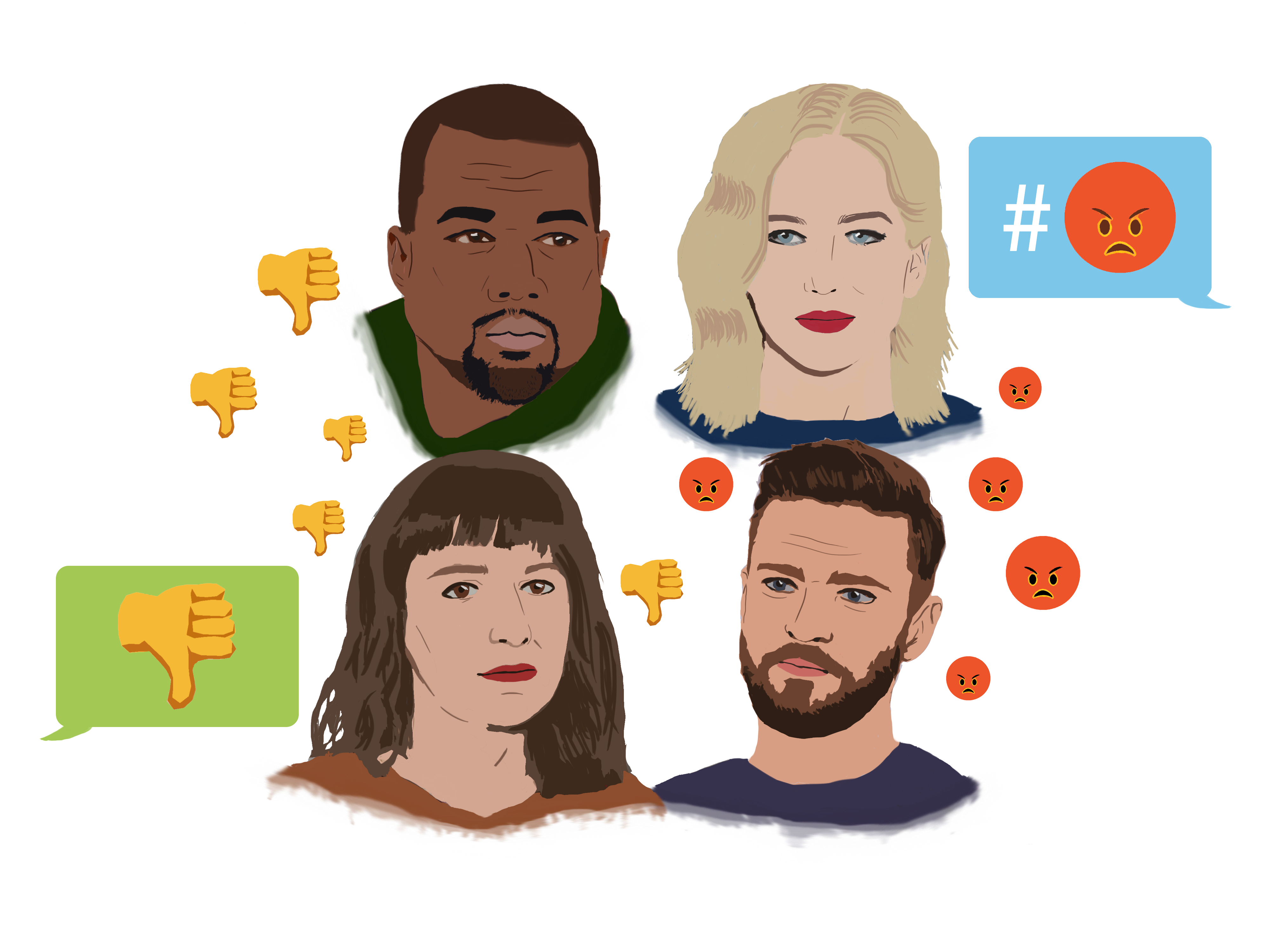

W hat do you think of when you hear the phrase ‘call-out culture’? Social media, for a start. Liberalism, probably. Man-hating, brain-washing, social justice warrior – maybe. In general, call-out culture refers to ‘the tendency to publicly name instances or patterns of oppressive behaviour and language use by others’ and has become synonymous with the ‘age of political correctness’ – whether that be good or bad.

Call-out culture comes from an inherently good place – the notion that we should not let discriminatory comments go by unnoticed, and that we should educate the people who make these comments. This is not necessarily the practice we see today, however. When a single bad tweet can end a career, or a past mistake can be dredged up to make you the laughing stock of the nation, something isn’t right.

To use the analogy of the prison system: calling someone out on social media and them subsequently losing their job, is akin to giving someone a 10-year sentence for a petty crime. Sure, they most certainly deserve some form of comeuppance, but does it fit the crime?

We banish and dispose of individuals from afar via social media, rather than engaging with them as people and helping them to see the error of their ways. Our ‘whack-a-mole’ approach to discriminatory comments, does not actually tackle the real problem. Institutionalised racism and sexism can’t be solved by sharing a Buzzfeed article about Gigi Hadid.

The world of Facebook, Instagram and the rest of social media is undoubtedly a world of constant display and observation. The desire to be embraced and praised by the community is intense; people dread being exiled and condemned. This has subverted the true point of ‘calling someone out’ and instead reduced it to an item on a to-do list, a reminder of your own personal level of social education – click ‘share’ and you’re done for the day.

Furthermore, there are such constantly shifting societal standards about what it means to be virtuous, that it feels impossible to set a definite standard. Of course some things, like Nivea’s recent advert in which their moisturiser seemed to promise to ‘lighten’ your skin, falls clearly on the wrong side of the line. Nonetheless, should Tina Fey have been berated for a two-minute SNL sketch in which she suggested eating cake instead of protesting? Sure, she could have used her platform more effectively, but should she be reprimanded so severely?

Call-out culture can also often have the opposite effect to its original intention; Trump’s early popularity was built almost entirely on the free media attention he received by people and news outlets criticising his comments. Far from this making him drop out of the race, it actually meant that he was able to reach a much larger pool of people, many of whom found that they shared his outdated and outlandish views. In fact, at many points during the election cycle, it seemed as if Trump was actively employing call-out culture as a way to harness the strength of the media and elevate his status.

The core issue with call-out culture, however, is that it doesn’t really change people’s true opinions. It just makes them more careful about what they put online, what they say on TV and to whom they talk.

In truth, we are simply not dealing with the systemic issues that plague our country, instead, we are using our social media accounts to remind ourselves that no, we aren’t actually bad people. There are other ways to help reduce discrimination rather than reducing individuals to tools of our own social advantage.

Image: Casey Linenberg